Transfer in Ballroom Dance:

Transfer Dance-Patterns

for Variety and Fun!

by Craig Rusbult, Ph.D.

My reason for writing this is to help you

Reduce Boredom by Increasing Variety.

the problem: Based on my experience when playing the role of “leader” in ballroom dancing,* I think most leaders (aka leads) feel uncomfortable when, less than a minute into a 4-minute song, they have led all the patterns they know so they must begin repeating. A leader doesn't want to make the dance boring for their partner. They want to make dancing more fun, and the adventure of variety can help this happen! 🙂 {* A feeling of discomfort – because I want to be more effective in helping each dance be a fun adventure for my partner – was stronger in my early days as a leader, but even now it hasn't disappeared. }

a solution: To increase the variety-and-fun for their partner, a leader can multiply the number of patterns that are available if they use transfers-of-patterns, if when they learn a pattern in one kind of dance, they transfer this pattern to other dances. For example, most patterns from one 6-step dance (waltz, rumba, mambo, cha cha,...) can work well in other 6-step dances. And we can transfer patterns from one 4-step dance to another. Using transfer-of-patterns is one strategy (among many) for increasing fun with dancing. {more about transfers}

a problem (for both dancers): Along with my partner, I also was bored when I knew only a few patterns, so I had to repeat these patterns (over & over & over & over) during an evening. Now I know many more patterns — although not nearly what is possible, what I've seen other dancers do, or I can imagine — but boredom still is a problem for a leader, because... Followers get to dance whatever is led by a variety of leaders, so they can have many “magical mystery tour” experiences, often wondering “what will happen next?” throughout the evening. But as a leader, I get to dance only what I know (nothing more), over and over.

variety with quality: Therefore, to increase fun and decrease boredom, for my partner and myself, I enjoy learning new patterns that work smoothly. A pattern will "work smoothly" when it's compatible with the physics-and-physiology of myself and (especially) my partner, when the physics allows a smooth transition from the direction she was moving to the new direction she will be moving after the change I ask her to make, and when she can make this change because it doesn't demand more of her physiology than she is capable of doing, and will enjoy doing, with her body (structural frame, muscles of legs & feet,...) and mind (in responding appropriately to my leads). {note: I will refer to leaders & followers as he & she, because that's been my experience, and it's usually (but not always) the gender-roles, and it's traditional, is linguistically easier, etc.}

Actually, dancing well requires physics-and-physiology-plus-psychology, as explained in more about leading & following.

For these reasons, from 1992 to 2012 – but with a long break (with a little ballroom dancing, but not much) between 1994 and 2012 – I've been thinking about ways to learn new patterns and teach new patterns. What are the options?

• While dancing, occasionally I experiment by trying new patterns. Sometimes they work, but not if they don't successfully pass the “reality checks” imposed by the requirements of physics-and-physiology, as described above.

• I watch other dancers, looking for “cool moves” I can imitate. This is difficult with live action, because it's tough to catch the details (e.g. was it led on the 1st-step or 4th-step of a 6-step pattern? and so on) in a one-time observation, because a skillful leader won't continually repeat the same cool move, over and over. And in a social situation, “practicing” with a partner is awkward because our dancing is less fun if the details of physics-and-physiology aren't done properly when I'm experimenting by leading a new move. So I rarely do this. / Compared with 1994, in 2011 learning new patterns was easier because of the many available internet videos, like on youtube. Some videos are taught well. But too often, the video teacher doesn't clarify important details. For example, they usually don't say whether it's led on the 1st or 4th step of a 6-count, because they don't count steps; or when they do count, instead of the most informative counting (saying “1_23,4_56”) they will say “1_23,1_23” (or “1_34,1_34” or, less helpful, “1234,1234”) or “slow _ quick quick, slow _ quick quick”, and this absence of valuable information-details makes it more difficult to learn quickly and well.

• I can ask a follower to “please show me what you know” by back-leading a pattern or explaining it. Unfortunately, she often knows how to follow a pattern (which requires special skills) but not how to lead it. Also, this request is awkward in many social dancing situations (although it shows respect for her experience & skill); typically it's more appropriate for a “practice” situation.

• Or in a class, live and in-person, a teacher can help us learn new patterns. But my experience with dozens of teachers, in Madison and Seattle, is that they aren't very effective in teaching lots of new patterns. Usually this is because they don't try; their classes move at a slow pace, and they don't provide memory-reminders that would make it easier for their students to practice-and-learn effectively outside the class time.

We (as learners and teachers) should be able to do better, and that's why I'm writing this page.

Using Transfer-of-Learning to Increase Variety

Teaching for Transfer: In 1994, I wrote a series of pages that outline a system I developed for helping students quickly learn

a wide variety of ballroom dancing patterns, with each having rhythm, timings, and movements that “work” so the pattern feels good and looks good. The basic strategy is teaching for transfer so when students learn a pattern in one kind of dance, they can transfer this pattern to other dances.

Two Kinds of Dances: This system

is based on my observation, in 1992-1994 when I was learning how to dance,

that most ballroom dances are in two categories (six-step or four-step) and dances within each category can share many of the same step-sequences.

Transfers of Patterns: For

example, many patterns from any six-step dance (waltz, rumba, boxtrot, cha cha, mambo, salsa,

nightclub two-step,...) can be used in other six-step dances, so there can be major transfers of learning. Similarly, in

four-step dances (foxtrot, east coast swing, country two-step,...) patterns can be moved from one dance to another. And sometimes patterns can be used in both 6-step and 4-step dances, as in hybrid mixes (see end of page) and adaptations.

non-Transfers: But sometimes a pattern cannot be easily transfered between dances, due to differences in tempo (if during one dance it's too fast for comfort, or too slow) or in the styling of a dance.

Rhythms: For both groups, 6-step and 4-step, several rhythms are used. A 6-step pattern can be danced in 6 counts (1 1 1 1 1 1) as in a waltz, or 8 counts (2 1 1 2 1 1, or 1 1 2 1 1 2) in foxtrot (box or moving), rumba, mambo, or nightclub two-step,* or the 8 counts (1 1 triple-step 1 1 triplestep) of cha cha. And a 4-step pattern can be modified from “slow,

slow, quick quick” in

6 counts (2 2 1 1) to “trip-le step, trip-le step, quick quick” (also basically 2 2 1 1) or “quick

quick quick quick” in

4 counts (1 1 1 1). {more about Rhythms & Tempos and Measuring & Changing Tempos}

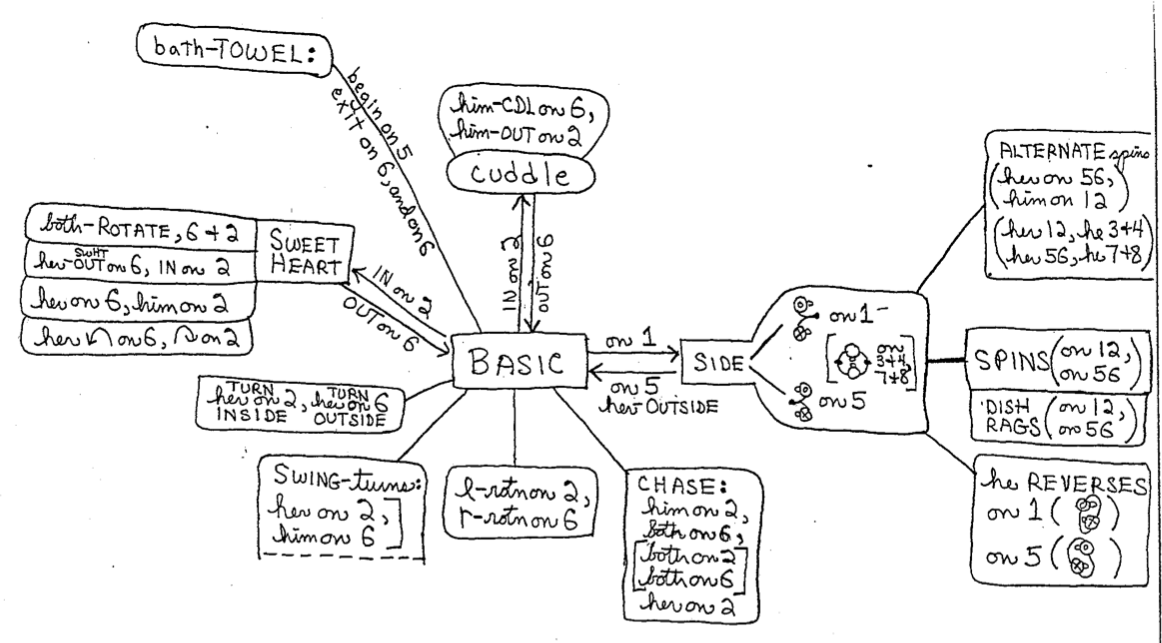

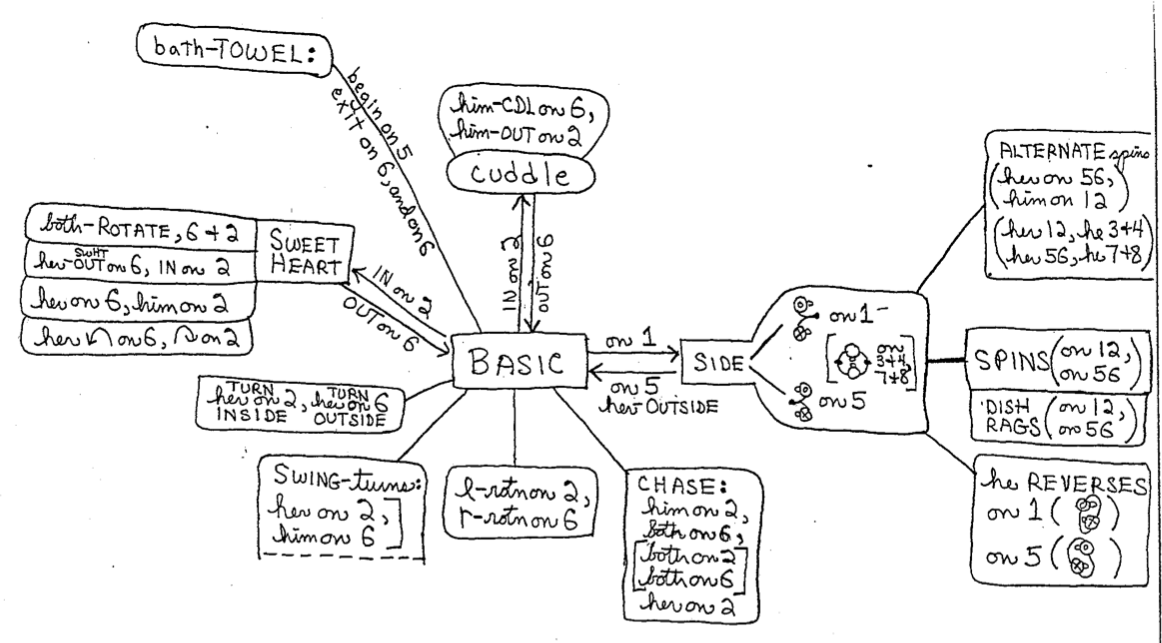

Also, Transition Diagrams (at end of page) illustrate the principle of a leader knowing the options for “what can be done next,” and making skillful real-time decisions about changing to “the next pattern.” This knowledge/skill is essential for making decisions that allow a smooth flow-of-motion from one pattern to another, by cooperating with our physics-physiology-psychology.

* A Complicating Factor: For some 6-step dances with 4-count music, different teachers use different rhythm-patterns, as with rumba that commonly is taught both ways, as "Slow Quick Quick" (S-QQ which is 211) and also "Quick Quick Slow" (QQS- which is 112). Some dances always use one or the other, as with S-QQ/211 (foxtrot) or QQS-/112 (mambo, cha cha) while other dances (rumba, nightclub 2-step) are taught both ways by different teachers. This can make a transfer more difficult, because (for example) if a particular pattern begins on the initial Slow (S) the leader must begin this sequence on the 1-step (of the 6-step pattern) and the musical 1-count with S-QQ; but with QQS- it's on the 3-step (of the pattern) and 3-count (of the music). This requires changing habits, and it makes transfer more difficult. / So maybe a leader who wants to make it less difficult should change all of their rhythm-thinking to either SQQ or QQS- ? Or maybe not. Instead I suggest becoming comfortable-and-skillful with both. Then if you want to transfer patterns from a QQS- dance (mambo, cha cha), you can count your rumba as QQS-, and this “matching of rhythms” will make the timing of step-transfers easier & better. But for a transfer of patterns from a foxtrot (or waltz, IMO) that's S-QQ, you can “match rhythms” by dancing your rumba as S-QQ.

A New Strategy: I've noticed this difficulty for a long time, beginning in 1993 with my second class in Rumba, because the first teacher used S-QQ, the second was QQS-. Then I was reminded of this difficulty in 2012, and now (in February 2015) I'm beginning to practice patterns both ways, to see if I can discover an effective way to mentally/physically shift from one rhythm to the other, and transfer patterns between all 6-step dances. Maybe this change will be simple, like just shifting my thinking from “lead on the 1-count [or 3-count]” to “lead on the [initial] Slow” but this may not work because Slow happens twice in each 6-step pattern, and usually only one of these will make the pattern work smoothly; this is why earlier I complained about videos that don't clarify whether a pattern is led on the 1-count or 4-count. / an update-comment: Although I think QQS- will work (for me) with most dances, and it seems essential for cha cha, I'm still finding it difficult, when waltzing, to not move forward or backward on the 1-step (of the pattern) and 1-count (of the music), which corresponds to S-QQ in the “4-count, 6-step” dances. And if I'm having difficulty, probably other leaders also will.

Variety in Leading: When dance-leaders know how to transfer patterns from one dance to another, this greatly increases the variety of the patterns they are able to lead. Learning the principles of pattern-transfer also will help followers, but it's especially useful for leaders. Knowing a variety of patterns lets a leader use the principle of mixing confirmations with surprises that is useful in dancing & music, humor & drama, in conversations and other areas of life. But although variety is a nice “bonus” it's more important to dance each pattern with high quality — so it feels good (for both of you) and looks good (for whoever is watching)* — by cooperating with your partner to make it work well.

Variety in Styling: Of course, the same pattern can (and should) have different styling when the dance-context changes, due to differences in music, tempo, rhythm, mood/attitude, skill of partner, and relationship with partner. In some ways this is analogous to variations in musical styles — as illustrated in a book I bought that included a phonograph record with the same tune played in many styles (swing jazz, be bop, blues, march, classical, dixieland, rock,...)* — and similar variations occur when the same dance pattern is used with different stylings in different dance-contexts.

* Two responsibilities of a leader are: don't injure your partner, and help them look good. Of course, how you do these will depend on your partner. Some of my partners seemed able to cope with anything I could do (within reason), no matter how complex or fast, but others have been less nimble and skillful. So I adjust. At two extremes... elderly ladies at a community center, who were less nimble-strong-skillful so our patterns were easier & slower, by contrast with... a younger lady at a church dance (held in the Monona Center with a medium-size dance floor plus a larger area with low-pile carpet that was smooth but with high friction, not ideal for a follower who must make fast movements that are unplanned) and after the dance I noticed she was wearing high heels; I said “if I was wearing those heels, within a few seconds I would have been on the ground with sprained ankles” and she said “with enough practice we can become very skillful at doing difficult things in heels.”

* Although using “variations on a theme” is useful for teaching, in dancing or music, the usual reason for musicians to adjust style is when they want to express themselves artistically. Musicians like to play their own version(s) of a song. For example, I've heard Summertime in a wide variety of styles by many different bands (i.e. teams of musicians) who each performed it with excellent quality to make wonderful music, in very different ways.

A Very Important Basic Skill

For both roles, but especially followers, it's useful to practice each rhythm-pattern while moving in every possible direction (forward, backward, sideways, turning left or right) with small steps or larger steps, while keeping the rhythm-pattern of your dancing, and keeping this in time with the music. You can practice this essential skill on your own, without a partner, just with the music and your own music-coordinated motions.

Learning and Teaching

During a two-year period in 1992 to 1994, I did a lot of ballroom/swing dancing, including lessons from many different teachers, first in Madison, then in Seattle for Summer '93, and back in Madison. I learned from all of them, about dancing and also teaching. Then I combined these ideas about learning-and-teaching with ideas from other contexts,* and I thought about how to combine what I was learning into a course. The main objective I wanted to achieve was helping leaders (and followers) learn many new patterns quickly and well, mainly by using transfer-of-learning, but also by developing improved techniques for teaching patterns.

* My learning-and-teaching experiences with juggling were especially useful because some of its teaching strategies would (with some adapting) be useful for helping students learn new dancing patterns. But useful insights also have come from teaching other mental-and-physical skills (music theory & improvisation and tennis) plus strategies (for learning, and for solving problems), and science (physics & chemistry & design process), math, and more.

Some of these ideas are summarized in pages written for class proposals in March 1994 and August 1994. Neither was accepted (in fact, I think the second was never even read-and-considered, in a one-person decision based on minimal knowledge) so I've never taught any formal classes, although I have done some informal “teaching” with friends.

Therefore, I'm hoping to discuss these ideas with teachers who have more experience. Although I have abundant experience with teaching in many areas (ranging from juggling to physics) and with learning in many areas (mental & physical, including ballroom dancing) and with observing teachers (of ballroom, and in other areas), it would be very useful to get feedback from skilled, experienced teachers of ballroom dancing. This would be greatly appreciated by me, and probably our discussions also would be useful for them.

Some Possibilities

In mid-2012, I started ballroom dancing again, and also thinking about how to revise-and-use my ideas from 1994. The revising began by adding comments to my pages from 1994 — those with " • " have some comments that are enclosed within [ ]s and are highlighted by color, like “[2012: Recently I've been thinking that instead of...]”. And I've made several pages of hand-written notes (for my own use) about a new-and-improved sequencing of patterns for a course.

Then I realized that what I wrote in 1994 is “too much” for most readers, so I've begun writing a shorter summary (but also adding some new ideas) and you can see an incomplete rough draft for parts of it below in the yellow box — for a class that could be taught in fall-2012 or 2013, with principles-and-patterns for some traveling dances (waltz & 6-step foxtrot, 4-step foxtrot) and stationary dances (waltz & rumba, cha cha).

an update on July 23, 2012: Currently I'm thinking it will be wise to delay detailed class-planning for awhile, so I can focus my time & energy on developing a website – Education for Problem Solving – to help students improve their thinking skills, because that is more important for me. Also, my first few times dancing in 2012 have been a humbling experience, compared with my unrealistic expectations that I would begin where I ended at my peak in 1994 — basically I'm doing fine, but 18 years of neglect have led to forgetting some patterns (with names I wrote on my Transition Diagrams in 1993-94) or forgetting the timings needed to make some of my experimental patterns “work well” (although many are working quite well) — so I'm feeling humble about offering to be a teacher of others, until I get more of these details figured out, re: my own dancing, and (more important) the details required to make more of the patterns work well. And that's a reason to be interested in collaborations. I've never claimed to be an expert in all phases of dancing and teaching, because I'm not; but I think the ideas outlined below (some borrowed, some invented) could be developed, in cooperation with others and combined with their ideas, into useful instruction.

Here is an update on August 25, after getting a “no” from the main dance instructor for UW's main dancing group, UWMBDA:* I've decided “no” for teaching a class alone. But I would like to talk about these ideas with other dancers and teachers. If a class arises from this (and if not, that would be fine with me), doing it with cooperative collaboration would produce a better class, and the process of designing-and-teaching the class would be more fun. / * He didn't even look at the ideas, or ask me to discuss them with him and with other dancers in the group, before rejecting the ideas. { Maybe I'm being cynical, but instructors who get paid (and want the income) have a vested interest in keeping their students dependent on the teacher for learning new patterns for each dance. If students become too independent, are able to transfer patterns from one dance to another, maybe they won't sign up (and pay) for classes specializing in each different dance? Maybe. Or maybe they just don't recognize the possibilities (and benefits) of teaching-for-transfer.

But writing a basic summary of some principles won't take as much time, so I have begun doing this (in 2012), to make an outline of ideas for the kind of class I would like to teach, or (as a learner) I would want someone else to teach. Here is a beginning:

The beginning of this page — it's an introduction to explain why I'm writing it in 2012 — includes important principles of physics-and-physiology followed by some observations about typical classes and teaching techniques. Below are additional comments about each of these, plus Movements with Rhythm and Principles for Transfer:

Physics-and-Physiology

Here are some quotations from the “details” page I wrote in March 1994, with some comments added [inside brackets] in 2012:

Try to develop skill [with frame & leading] early — for the benefit of yourself (so you can learn the principles and patterns) and for your partners (so they will have something worthwhile to “respond to” and can learn to follow skillfully). ... Let your partner know what you want to happen next, soon enough that she can do it — i.e., soon enough that she is not already physically committed (due to her momentum and direction-of-stepping) to doing what she would need to do if there was a continuation of the previous pattern. ... Make easily recognizable differences between the leads for one pattern and another. [This timing-and-clarity of leading will help minimize the “backleading” that occurs when a follower anticipates a lead and begins to do a movement that wasn't led.]* The “strength” of a lead — whether it physically moves a partner in a certain direction, or merely “suggests” what to do so she can respond (either consciously or in muscle memory) and do it independently — will depend on the pattern, and on the skill and style of yourself and your partner. ...

* [Skilled following is not passive, it's a very active process that requires alertly aware observation of cues, combined with quick interpretation of the cues and almost-instant responsiveness, plus coordination and physical agility. As you can tell, I'm amazed at the skill of good followers, am truly impressed.] [Backleading should be minimized when it's uninvited, but it can be invited by a leader who wants to learn new patterns from a follower.]

A good frame defines and maintains a relationship between dancers, so the two of you can “move as a unit” for better technique and for instant communication of easy-to-feel cues for leading-and-following. ... How? Be solid but relaxed. ... With relaxation, only the muscles that need to be used are being used — no more, no less. Because muscles are not constantly fighting each other (in an internal tug of war) there is more speed, strength, grace, and endurance. Also, there is a better message of “body language and mental attitude” communicated to your partner, thus allowing your dancing to be more mutually enjoyable.

{terms: My use of he & she, for a leader & follower, is explained earlier.}

Techniques of Teaching

I think students learn more quickly when they have take-home reminders of the principles & patterns being taught in a class. These reminders could be verbal and/or visual: written explanations of principles, and explanations of patterns plus (when this is useful) diagrams for the patterns. And compared with 1994, in 2012 (due to the higher quality & lower price of video cameras and editing programs) it's much easier to make instructional videos that offer many benefits, compared with words or static diagrams.

In classes without these memory-reminders, a limitation on learning is the problem of “mental overload” when learning new movement-patterns during class, if there is too much to mentally remember, so (due to limited class time) the new patterns are not yet solidly known in mental & physical memory. If teachers pace a class very slowly, so students have enough time to thoroughly learn new patterns in their mental memory & physical memory, a learning of new patterns will occur very slowly. But a combination of in-class practice plus after-class practice (mental & physical) with reminders (in written explanations + diagrams, or video) should help students (especially leaders) learn new patterns much more quickly.

MORE — In the future, I'll describe other ideas about techniques to improve efficiency and to achieve other educational goals. One idea, outlined here very briefly, is that most rotation-patterns (and many other patters) are identical for leads & follows, they're just offset in time: what a leader does at one time, a follower does at another time. Therefore, instead of wasting valuable in-class time by explaining each pattern separately, a teacher can have the entire class learning-and-practicing the same set of patterns. Then dancers get together in couples, to practice doing these patterns as a two-person unit with leading-and-following, with the proper "offsets in time." Later, I'll explain this dancing principle (and associated teaching strategy) more thoroughly, with examples & details, along with other techniques for teaching.

Movements with Rhythm

An essential skill for dancing is an ability to move in consistent rhythmic patterns, so your stepping-rhythm will match your partner's rhythm and (as explained in the next section) the music's rhythm. The main way you improve this ability is to use it, with or without a partner. It's easy to practice this in solo moving-with-rhythm, in free dancing without a partner; just put on music with an appropriate tempo for a particular rhythmic pattern (the basics are described earlier) and practice keeping this rhythm pattern (in time) while (in space) you are moving in the wide variety of dance patterns (moving backward, forward, sideways to left or right, rotating left or right,... slowly & quickly, with short strides & longer strides) that might be used while you're dancing with a partner.

This practicing is valuable for leaders and (especially) for followers.

For leaders, it will help you avoid getting confused and mis-leading your partner by changing the dancing rhythm in ways that you had not intended, in ways that won't work with the physics-and-physiology of your confused partner.

For a follower, you can practice moving in the many possible ways that you might be led while dancing, so you can cope with “whatever happens” without taking extra steps. For a novice, extra steps tend to occur because they help you keep your balance while moving in a dance pattern, in ways that cooperate with your physiology and minimize any potential for injury or “falling down” embarrasment. These extra steps are the natural way of moving that you have practiced your entire life. To overcome these instincts, you must practice a new way of moving gracefully and confidently in new time-and-space ways, with complex dance-patterns and a consistent rhythm. The movement-practice I recommend can help you do a wider variety of movements without extra steps, so you can maintain the rhythmic step-pattern.

This is an important skill. When I returned to dance-leading in 2012, one of my discoveries is that many followers simply cannot “keep the rhythm” consistently, so they have no chance of consistently following my leads, or those of most other leaders. If you want to become a reasonably skilled follower, keeping the rhythm-pattern is a minimum requirement, a basic starting point.

Dancing with Music

Improving your musical skills will help you dance in ways that cooperate with the music. When you and your partner each “feel the music” and are dancing with it, this makes it easier for you to dance with each other.

At a basic level, you should learn how to recognize the 1-count of each musical measure, and know whether a measure has 4 counts (usually) or 3 counts (as in a waltz).

At a level that's a little more advanced, but is easy when you become more musically aware, you can listen for the phrasing that occurs every 2 measures. In 4-count music, 2 measures is 8 counts, so coherent phrases — these are sort of like “sentences” in talking — occur every 8 counts, which is 2 measures. Phrasing also occurs in multiples of 2 measures (so it's 2, 4,...) to form coherent “phrasing units” (analogous to paragraphs?) that fit together well, with a clear beginning & ending. Of course, with 3-count music the 2-measure phrases begin every 6 counts.

This 2-measure phrasing is important for dancing. A 6-step dancing pattern requires 2 measures of music; usually this is 8 counts, but it's 6 counts for a waltz. A leader should begin a 6-step pattern at the beginning of a 2-measure phrase. / In terms of priorities, it's most important to begin a 6-step pattern on the 1-count of a measure. It's less important, but still is important, to begin at the beginning of a 2-measure phrase. These two beginnings (on the 1-count of a 2-measure phrase) make it easier for your partner to follow your leads, because she can stay in-sychronization with you and also with the music. When this threesome (music, leader, follower) are all in-synch with each other, your dancing will feel better (for both of you) and (for spectators who know music & dancing) it will look better.

Phrasing is less important with 4-step patterns. If you begin on any 1-count, your 4-step pattern will work well if it's in 4 counts ("quick quick quick quick") or 6 counts (like "slow slow quick quick" or with "slow" replaced by "triple-step"). With 4 steps in 6 counts, the beginning of a 4-step pattern shifts back and forth between the 1-count and 3-count, but this cannot be avoided. With 4 steps in 4 counts, you can always begin a pattern on the 1-count.

These principles are generally accepted. But there is a range of opinions for some principles, regarding a Matching of Styles - Music and Dancing.

Principles for Transfer of Learning

Some basic principles, including principles for dance-rotations and for other types of movements, will help dancers (especially leaders, but also followers) transfer what they learn from one dance to another. This is consistent with research-based principles for transfer of learning, such as using Conditional Knowledge & Organized Knowledge and much more. Here are some useful principles:

• Basic principles of rotation — it's easier and more “natural” to begin turning left when stepping forward on your left foot or backward on right foot, and begin turning right when stepping backward on left foot or forward on right foot — can be used in all dances. And students can learn special techniques (pivots, step-behinds,...) for other kinds of rotations in turns or semi-turns.

• Also, when you and your partner are facing each other, the kind of turn that is “natural” for a leader is also best for the partner. But if you're facing the same direction, as in a cuddle or sweetheart position, you must choose who will do the easy turn, and it's courteous for you (as a leader) to make things easy for your partner, while you use a “special technique” to make it also work for you; doing this is challenging for a leader because you must do the opposite of your habits for “doing what is natural” that you have established through practice.

• If you are facing your partner but she is “offset” to one side, you can rotate in one direction but not the other; if during a rotation you will face each other, the turn will work, if not it won't. For example, if she is offset to your left, during a left-rotating turn you will face each other and it will work. But if she is offset on the right side of you, a right turn will work. There also are principles for moving diagonally forward in the line-of-dance, first on one diagonal and then on the other diagonal, making forward progress in a zig-zag “sideways W” pattern by using quarter-turns.

All of these principles, and more, can be taught using a combination of logic (based on principles of physics-and-physiology) and experimenting (you try things and observe how well they work) along with letting your body-and-mind “figure out the details” as with "inner game" approaches like the one in my paragraph about analysis-and-synthesis of juggling.

I.O.U. — More could be said in each of these paragraphs, and others, but that's all for now. Also, above you'll find Rhythms and Variety in Leading (with some surprises) and Variety in Styling and below, Matching Styles and Hybrids. |

Matching Styles — Music and Dancing

Some dancers, but not others, think some songs should be reserved for specific dances. Sometimes musicians specifically play a song (or compose it, or arrange it) to be used a specific dance – for tango, cha cha, salsa,... And sometimes, even though the musicians didn't intend for a matching of song-with-dance, dancers interpret a song to be more suitable for a specific dance. When this interpretation is at the level of “community” almost all dancers will be doing the same dance (due to their personal style-matching preference and/or a desire to conform) even though the song's tempo would also allow other dances. And this variety does happen sometimes, with different couples doing many different dances during a song.

Earlier, I described "generally accepted" principles for Dancing with Music, and contrasted this with "a range of opinions" for Matching Styles. In many ways this range is analogous to categorizing in other areas of life, where the extremes of a spectrum are Splitters and Lumpers. At one end, a Splitter decides that each song should correspond to one dance, and only one. At the other end, a Lumper thinks the only relevant characteristic of a song is its tempo, so a song at 120 bpm can be used for many different dances, for any dance that includes 120 bpm within its range; also, the suitable "range" of each dance is open to interpretation, and is wider for social dancing than for competition.

Of course, instead of a simple one-dimensional spectrum moving smoothly from splitters to lumpers, the reality is more complex; it's multi-dimensional with many factors affecting how a person feels, in various situations, about combinations of song-and-dance.

Here are some applications, based on my own experiences. Usually (but not always, it depends on the song and situation) I tend to be a lumper, but with Variety in Styling and in choice of patterns. Occasionally a partner will protest that "this song isn't a Cha Cha, it's a Rumba." When this happens, sometimes my initial response is to think "don't be inflexible and silly, just relax and enjoy a Cha Cha." Although I think the second part of this thought – to relax and enjoy – is a useful general strategy for all dancers (especially followers), it's not wise for a leader to say the first part of it, and in fact it's not even justifiable (or socially useful) to think it, because for me to think she is "inflexible and silly" is no more warranted than for her to think I am "insensitive and (regarding the music, dancing, and/or her) unaware." Instead, usually we compromise; I change to leading Rumba, and we both enjoy it, or we enjoy a Cha Cha because she was silent so I didn't know she would prefer a Rumba. Or to avoid her "silent toleration" (or "silent simmering" if she REALLY wanted to Rumba), sometimes at the beginning of a song I'll suggest 2 or 3 options and ask what she wants to do, so we can briefly discuss and then agree.

Adding Variety with Hybrids

Pure (6-with-6 or 4-with-4) Hybrids: Because "many patterns from any six-step dance (waltz, rumba, boxtrot, mambo,

cha cha,...) can be used in other six-step dances," during one type of dance (waltz,...) you can use a pattern that is unusual for this dance but is common in another six-step dance — if it can be suitably adapted so it feels good and looks good — for variety and a change of pace that mixes confirmations with surprises. In a similar way, dancers in Country Two-Step often mix patterns from two 4-step dances, foxtrot and swing, and the resulting hybrid is what you typically see on a dance floor; they also can use patterns from 6-step dances, if these are adapted to make them fit smoothly into the 4-step dance rhythms.

A Mixed (6-within-4) Hybrid: During a foxtrot with 4-step patterns in 4 counts (1 2 3 4) a leader can temporarily shift into 6-step waltz patterns in 6 counts (1 2 3, 4 5 6) for a temporary period lasting 12 counts [or 24, 36, 48, ...] and then shift back into 4-step foxtrot patterns. When this is done well (and it isn't difficult) it "works" and is a nice change of pace that adds variety. Yes, throwing 3-count patterns into 4-count music is a bit unusual, but when it's done occasionally it can be a refreshing change of pace; this is one way, among many possibilities, to add some variety to the dancing experience of your partner, contributing to the spice of life by "mixing confirmations with surprises."

Contra Dancing and More

For a different kind of variety, many people (including me) enjoy contra dancing. This has more of a “community” feeling because there are many quick changes, during each song, between dancing in couples and dancing with others in a larger group. Everyone is a follower of the dance caller, who explains each pattern in a sequence (and lets dancers “walk through” the sequence in a rehearsal) before the dancing-with-music begins. { Contra Dancing in Madison & Wisconsin } { for other kinds of dancing, click and change the "Events" menu to "Dancing" }

Ideas from 1994:

Most of my writing about dance-teaching was at two times in 1994,

and below are the main results, with each link below opening the new page in its own new window, so this page remains open in this window:

written in March 1994,

for Wisconsin Union Mini-Courses |

written in August 1994,

for UWMBDA, UW-Madison Ballroom Dance Association |

proposal (this is fairly detailed) •

2012 Proposal { see the IOU } |

proposal (this is an informal rough outline) • |

| details (principles

for dancing and teaching) • |

|

rhythms (variations

for 6-step and 4-step dances)

change music tempo with Audacity (written 2008) |

|

| system (a beginning,

with much less detail than in August; but

a few of these ideas are missing in August) |

matrix (a visual

summary of the system described below)

system (showing

some possibilities that can be developed)

[a thought in 2012: I wish I knew now, what I knew in 1994.]

diagrams (not organized

or labeled, in pencil not ink) |

deciding “the next pattern” for improvised dancing

To make a dance interesting-and-enjoyable for their partner, a leader must know patterns AND make skillful decisions about “what pattern to do next.” To improve my own leading in 1994, I made “transition diagrams” to show options for “what can be done next,” and I used these diagrams to do mental rehearsing before a dancing event, and occasionally between dances during the event. For example, the right-side diagram shows, for a Cha Cha, that from the BASIC position there are 8 options (on my diagram, although more than 8 in reality), and after doing a "SIDE" (but not before this) there are 3 new options, shown on the far right.

To make a dance interesting-and-enjoyable for their partner, a leader must know patterns AND make skillful decisions about “what pattern to do next.” To improve my own leading in 1994, I made “transition diagrams” to show options for “what can be done next,” and I used these diagrams to do mental rehearsing before a dancing event, and occasionally between dances during the event. For example, the right-side diagram shows, for a Cha Cha, that from the BASIC position there are 8 options (on my diagram, although more than 8 in reality), and after doing a "SIDE" (but not before this) there are 3 new options, shown on the far right.

improvisation vs choreography: Sometimes two dancers decide, before a dance, exactly what they will do, by pre-deciding the entire sequence of patterns; this is very common in competitions, is rare in social dancing. The two kinds of dancing – improvised and choreographed – are different in some ways, but are similar in many ways.

iou – Soon, maybe in late-April 2024, I'll develop other explanations of how to use these diagrams, so other leaders (not just me) can understand them and use them. And eventually I'll make new diagrams, revised to make them better. Or in a quicker temporary-revision, I'll do cut-and-pastes (from the “mixed” sheets that include waltz, cha cha, rumba,...)

to gather all diagrams for each dance together in one place, to make one page for waltz, and others for cha cha, rumba, and so on.

Transition Diagrams show possibilities

for “what to do next” in...

waltz rumba cha

cha 8-count swing swing 4-count plus

transitions between dances mixed

sheets (with several dances.

To make a dance interesting-and-enjoyable for their partner, a leader must know patterns AND make skillful decisions about “what pattern to do next.” To improve my own leading in 1994, I made “transition diagrams” to show options for “what can be done next,” and I used these diagrams to do mental rehearsing before a dancing event, and occasionally between dances during the event. For example, the right-side diagram shows, for a Cha Cha, that from the BASIC position there are 8 options (on my diagram, although more than 8 in reality), and after doing a "SIDE" (but not before this) there are 3 new options, shown on the far right.

To make a dance interesting-and-enjoyable for their partner, a leader must know patterns AND make skillful decisions about “what pattern to do next.” To improve my own leading in 1994, I made “transition diagrams” to show options for “what can be done next,” and I used these diagrams to do mental rehearsing before a dancing event, and occasionally between dances during the event. For example, the right-side diagram shows, for a Cha Cha, that from the BASIC position there are 8 options (on my diagram, although more than 8 in reality), and after doing a "SIDE" (but not before this) there are 3 new options, shown on the far right.